This month, let’s talk about the Black Phoebe. This bird is a member of the flycatcher family. If you live in the Sacramento Valley, you probably have seen them in your yard or in a neighborhood park. Black Phoebes seem to do well living among humans and are not as ‘shy’ as other species of flycatchers seem.

Adult Black Phoebe, Image by Larry Hickey

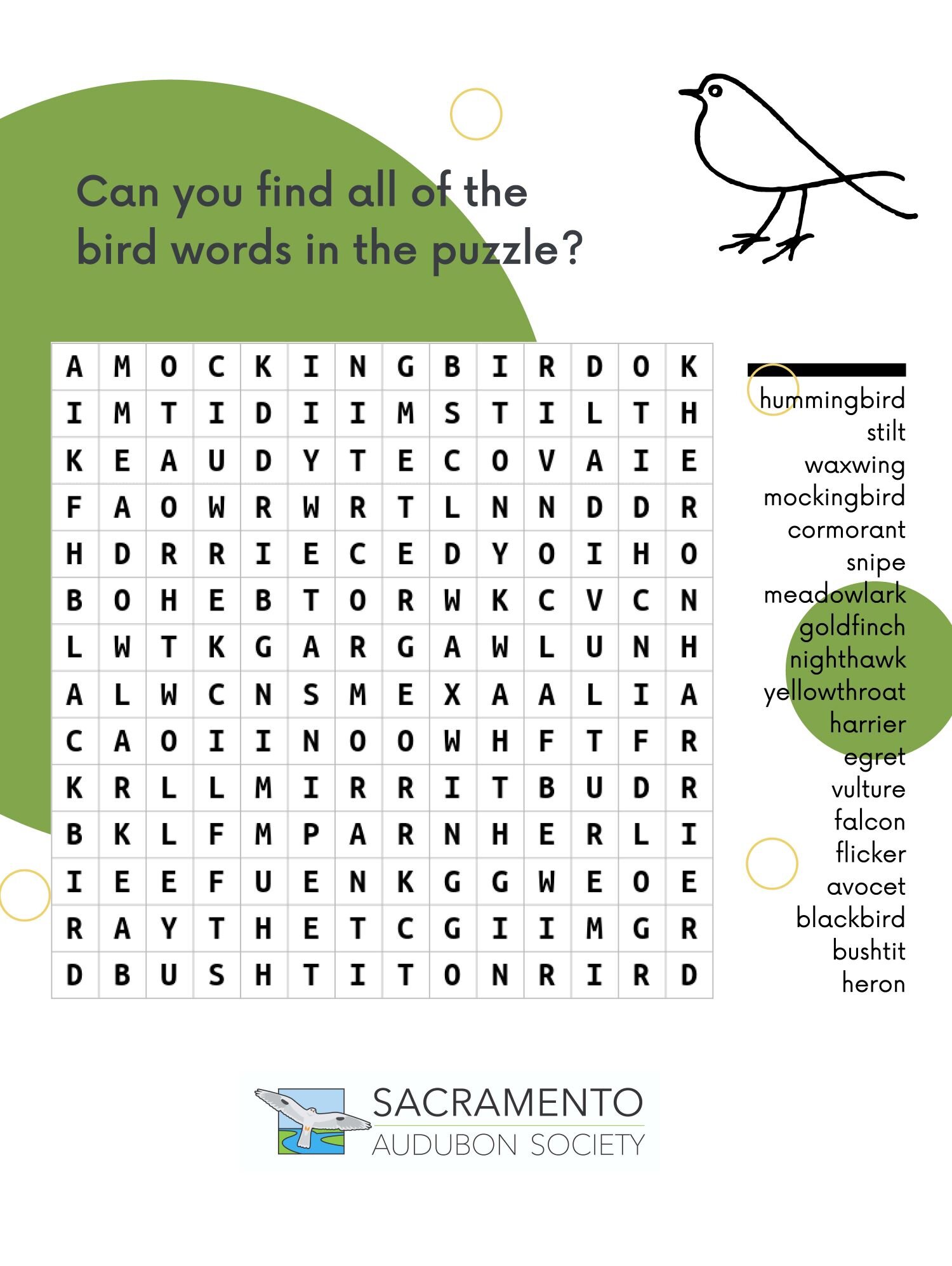

What do Black Phoebes look like?

Black Phoebes are black on their heads, wings, and upper breast. They have a white contrasting belly. Their bill, legs, and feet are black. Males and females look the same. Young (or juvenile) birds have brown feathers (or plumage) and have two light brown wing bars. The feathers of young birds will darken as they age.

Juveniles are brown and have light-brown wing bars, Image by Mary Forrestal

Where do Black Phoebes live?

The range of the Black Phoebe is from the southern Oregon coast, into California, and down through Central and South America. There are also populations living in parts of the southwestern United States. While there are a few populations that migrate to warmer climates for winter, most Black Phoebes remain in the same area year-round.

Black Phoebes almost always live near a water source. This is because they use mud to build their nests and because water attracts the insects that they eat. They live near streams, creeks, ponds, rivers, and along coastal areas. However, they also are often found living near people’s homes or in neighborhood parks. Just as long as water (or mud) is available, Black Phoebes seem satisfied.

Black Phoebes often build their nests on vertical surfaces and favor sites with overhead protection. In natural habitats, Black Phoebes nest in rock faces, coastal cliffs, boulders, or tree hollows. In urban or suburban areas, they have adapted well to nesting in man-made structures, such as eaves of buildings, abandoned wells, and irrigation canals (or culverts). By using mud, they can plaster their nests onto walls under the eaves of buildings, creating a perfect nest site. Black Phoebes frequently come back to the same nest or nesting spot year after year! Their nests are built well and last because they are strong. Black Phoebes are also quite territorial; so you usually won’t find another pair nesting close by.

It’s the Black Phoebe female that constructs a cup-shaped nest. She is also the one who sits on the eggs to keep them warm (this is called incubation). The Black Phoebe’s nest has an outer shell made of a mixture of mud and grass and is lined inside with soft plant fibers and/or animal fur or hair. When the young hatch, both parents are active in feeding their babies.

Juvenile Black Phoebe, Image by Daniel Lee Brown

What do Black Phoebes eat?

The main diet of the Black Phoebe is insects, mainly flying insects. They will eat bees, wasps, flies, beetles, bugs, grasshoppers, crickets, dragonflies, termites, and spiders. If you see one out in the open, calling frequently, perched low, and dipping and fanning its tail, it is probably busy scanning for insects to eat. When Black Phoebes spot an insect, they quickly take flight, chase the insect, and often catch it in mid-air! Occasionally, Black Phoebes will look for insects while they are on the ground; but, most of the time, they look for food when perched on low branches or on other low perches. Black Phoebes will also catch insects when they are flying over bodies of water. They will sometimes hover in the air and grab spiders on plants or trees. Black Phoebes have even been seen catching and eating small minnows just below the water’s surface!

What do Black Phoebes sound like?

Black Phoebes are quite vocal and have a familiar song and calls. They also use a contact call that is heard sometimes when two birds are flying close to each other. Kaufman describes the call note as a “sharp ringing peep” sound and the song as “thin, shrill whistles.” You can listen to their song and calls below:

These songs and calls of the Black Phoebe are from xeno-canto. More Black Phoebe vocalizations can be found at xeno-canto.org/species/Sayornis-nigricans.